This content is also available in:

Italiano

Português

Čeština

Română

Türkçe

Potential false positives

Although the clinical implications of false positives seem less significant than false negatives, they cause unnecessary anxiety to patients and may lead to unnecessary excisional treatment, which is now known to increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes in pregnancy.

Although the risks are associated with large excisions rather than LLETZ (Castanon et al. 2014), it is clearly important to avoid false positive cytological reports.

|

The key to avoiding false positives is familiarity with the full range of reactive and metaplastic processes that involve the cervix in the absence of neoplasia. |

This is obvious for primary screeners who are exposed to the full range of samples on a regular basis but it is equally important for pathologists to be familiar with the many benign, reactive and metaplastic changes that are regularly and correctly reported by cytotechnologists as negative.

It will also be important in the context of primary HPV screening when it will be necessary to give confident negative reports in the knowledge that all the samples are high-risk HPV-positive.

Potential false positives are caused by the following:

- Reactive inflammatory changes (e.g. atrophic vaginitis, follicular cervicitis, endocervicitis, repair/regeneration)

- Metaplasia (e.g. immature squamous metaplasia, tubal metaplasia, tubo-endometrioid metaplasia)

- Endometrial cells especially from the lower uterine segment

- Inflammatory cells (e.g. lymphocytes and histiocytes)

Reactive inflammatory changes that may mimic neoplasia

Atrophic changes

- Atrophy is frequently associated with mild inflammation, which is usually sub-clinical and does not require treatment.

- Hyperchromasia and mild atypia may be seen along with cytoplasmic orangeophilia (Figure 10.5 a) as described in Chapter 9b. [Link to Chapter 9b – Cervical cytopathology: normal cytology and benign reactive changes]

- The NC ratio may be relatively high but should be consistent with atrophic epithelium (Figure 10.5 a).

- The pattern in atrophic vaginitis is uniform throughout the liquid-based or conventional preparation, which is the key to avoiding false positive reports in this situation.

- Sudden changes of cell groups with hyperchromatic or irregular chromatin should be sought and reported if present. [Link to Chapter 9c – Cervical cytopathology: cytological abnormalities]

Non-specific and cervicitis due to infections

- Any form of cervicitis in a woman during reproductive life will result in a shift to the left and an excess of immature metaplastic cells compared with mature superficial cells. This is demonstrated by the reaction to Trichomonas vaginalis, which may mimic HSIL usually moderate rather than severe (Figure 10.6 b).

- Endocervicitis is characterized by loss of mucin secretion by columnar cells, which makes them look more like immature squamous cells sometimes mimicking HSIL. This may be seen in and around benign endocervical polyps (Figure 10.5 b and c).

- Repair is characterized by vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and regular nuclear membranes as illustrated in Chapter 9b Figure 13 (a). These features may be extreme and confused with malignancy (Figure 10.5 (d). [Link to Chapter 9b – Cytopathology: normal cytology and benign reactive changes

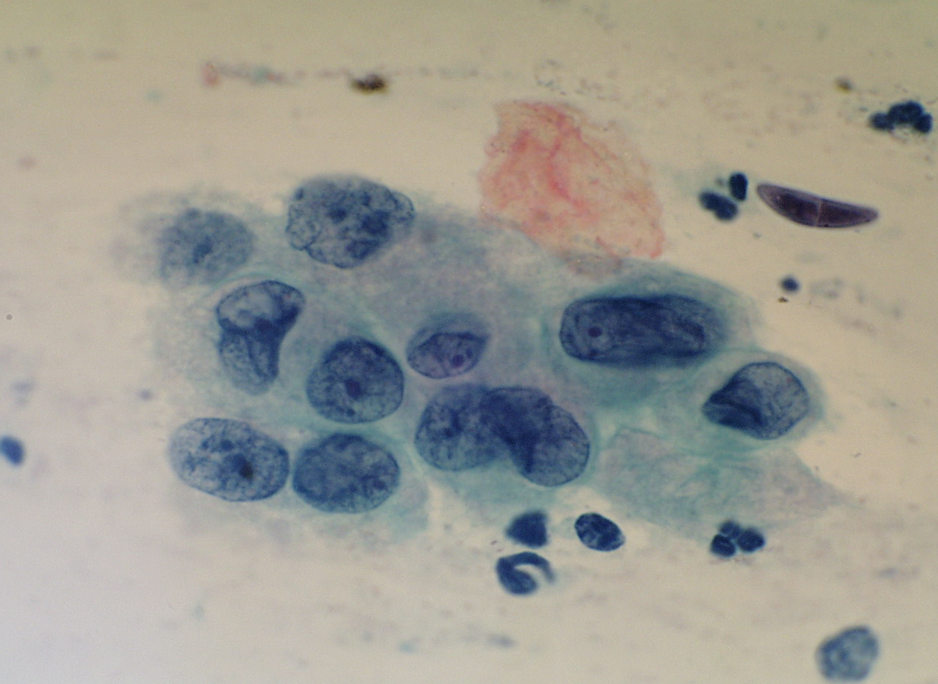

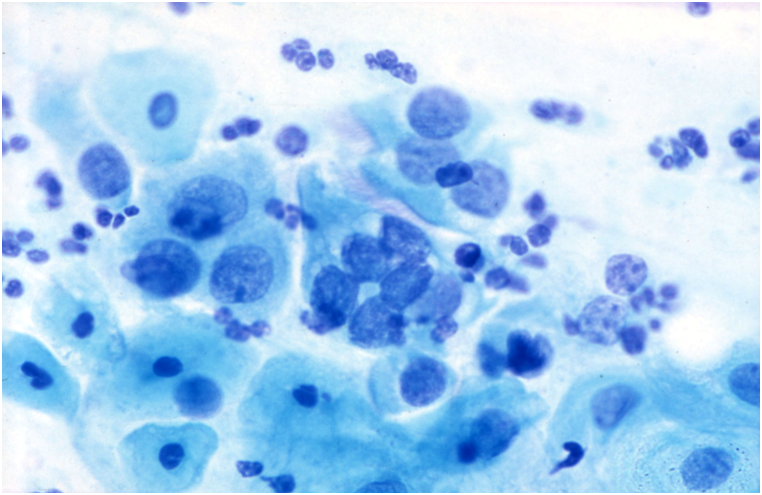

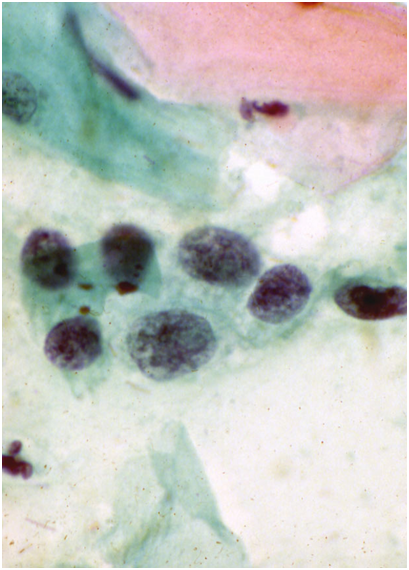

Figure 10.5 gives examples of benign reactive changes that are at risk for misdiagnosis as HSIL or malignancy

Degenerate hyperchromatic nuclei with a low nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio make HSIL unlikely in (a) and (b). Karyorrhexis is seen in the atrophic cell group (a), which is typical of atrophic vaginitis; this is easier when the pattern of the entire slide is similar. Pseudomultinucleation with abundant cytoplasm and a low nuclear/cytoplasmic is seen in (b). The chromatin and membranes are even in the small vacuolated glandular cells in (d). The chromatin pattern and membranes are regular in (e) and there is no pseudostratification to suggest CGIN. Prominent nucleoli in (c) are typical of repair; nucleoli are well defined in (f), the membranes are regular and nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio low. Apart from (a) and (d) none of these were reported as negative; (c) was misdiagnosed as suspicious of adenocarcinoma; (f) was misreported as moderate dyskaryosis and Trichomonas noticed (elsewhere on the slide) on review; (b) and (e) were reported as borderline.

Metaplastic changes

Immature squamous metaplasia

- Immature squamous metaplasia is the commonest pitfall and may be difficult to distinguish from HSIL especially moderate dykaryosis or HSIL favour CIN2. This is a particular problem with ThinPrep LBC as reflected in responses to the slide seminar at the BSCC terminology conference [Link to 10.3 Slide seminar].

- The distinction between HSIL and immature metaplasia has been considered in Chapter 9c in the sections on ASC. [Link to Chapter 9c – Cervical cytopathology: cytological abnormalities]

- Attention to the regular nuclear chromatin, well-defined but regular nuclear membranes (especially in ThinPrep LBC), prominent nucleoli and normal nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio expected for a metaplastic cell can usually resolve the issue.

- Immunostaining with p16/Ki67 can help distinguish immature metaplasia from SIL (Schmitt et al 2011).

- Two particular pitfalls are described here in this respect: i) the appearance of immature metaplasia in ThinPrep LBC, which can be confusing to the inexperienced observer, and ii) the shift to the left that is a feature of non-specific inflammation and infections.

Figure 10.6 Atypical immature metaplasia (LBC)

A LBC sample reported as moderate dyskaryosis/HSIL favour CIN2 that was found on cervical biopsy and LLETZ to be HPV only without CIN can be examined as a scanned slide [Link to win.eurocytology.eu/virtualslides/gyn/vs-031]. Cytology was reviewed as HPV change in squamous metaplasia, which could be regarded as ASC-US.)

Atypical immature squamous metaplasia

The term atypical immature squamous metaplasia has been used in the past for histological biopsies, which corresponds to the difficulty of distinguishing immature metaplasia from SIL in cytology.

Immunostaining for p16 and Ki67 (Duggan et al. 2006) or CK17 and p16 (Regauer & Riech 2007).) and can distinguish immature metaplasia from LSIL and HSIL in the majority of cases. [Link to Chapter 12 – Cytology in a multidisciplinary setting]

Tuboendometrioid metaplasia

Tuboendometrioid metaplasia (TEM) and, less frequently, endometriosis may be seen on the cervix especially after procedures such as LLETZ and cone biopsy (Ismail 1991; Hirschowitz et al. 1994).Figure 10.7 (a-f) Endometrial and tubal metaplasia mimicking HSIL

Figure 10.7

Tubal metaplasia

- Tubal metaplasia may be seen in the absence of TEM when it may mimic HSIL.

- Cytologically, the cells have plump enlarged nuclei. Basal plates can usually be seen even in the absence of cilia, which are diagnostic of tubal cells.

- Tubal metaplasia with inconspicuous cilia and basal plates may be a cause of false positive reports (Figure 10.8 b-c).

Figure 10.8

Endometrial cells

Endometrial cells may be a cause of false positive reports when they are seen outside the dates expected by date of the last menstrual period and when they do not present the classical appearances illustrated in Chapter 9b.

Two situations when endometrial cells have presented pitfalls in diagnosis are illustrated below: i) IUCD changes when the presence of a device was not known and ii) lower uterine segment sampling, especially when the endocervical canal is shortened after excisional biopsies of CIN.

Figure 10.9

Inflammatory cells that may mimic HSIL

Histiocytes

Histiocytes may have somewhat hyperchromatic nuclei that mimic immature metaplastic cells. Attention to the arrangement and cell separation of the whole cell group helps recognizing them as well as the high-power appearances.

- Histiocytes are typically seen at the end of menstruation and may be described as an exodus pattern.

- Similar sheets of histiocytes may be seen at any time of the menstrual cycle with certain forms of oral contraceptive.

- The NC ratio is lower than HSIL and the nuclei tend to be bean shaped and indented.

- Chromatin is finely granular, nuclear membranes are even and nucleoli may be present.

- Cytoplasm is usually pale and amphophilic but may be orangeophilic, mimicking squamous cells

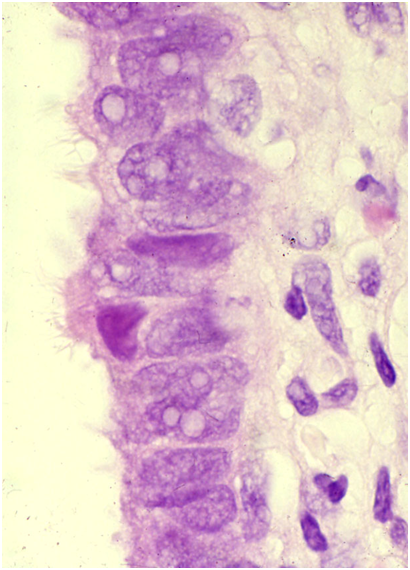

Lymphocytes

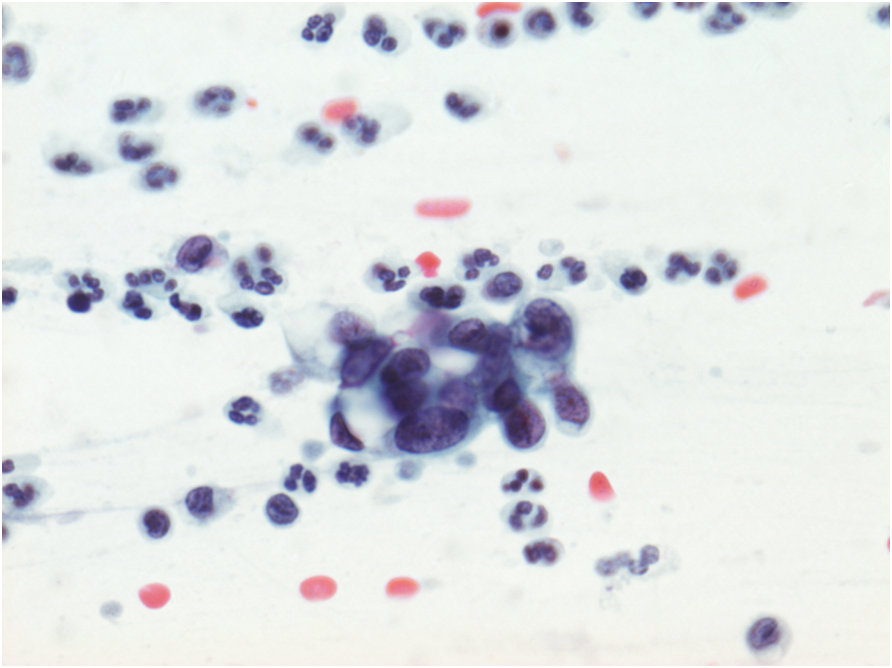

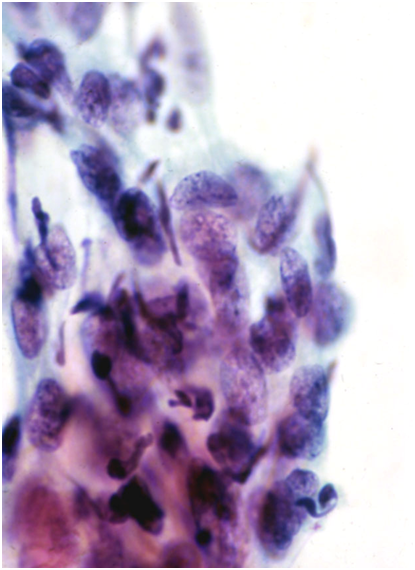

Lymphocytes in the aggregates seen in follicular cervicitis may cause a problem if tingible-body nuclei cannot be found. The typical finely granular chromatin pattern of small lymphocytes, associated with larger immature lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli abutting the nuclear membrane, is distinct from stromal endometrial cells and HSIL.

- Lymphocytes are seen in follicular cervicitis and may mimic small cell HSIL.

- The key to recognizing them is the presence of tingible-body macrophages in a mixed population of large and small lymphocytes.

- The cells may be clumped together in LBC samples rather than dispersed as seen in conventional smears.

- Lymphocytes have a thin rim of cytoplasm that is inconspicuous on alcohol-fixed stains such as Papaniculoau.

- Follicular cervicitis is most often seen in atrophy or in young women with Chlamydia infection.

Figure 10.10 Inflammatory cells mimicking CIN

(a) Histiocytes in a normal smear

As will be obvious from the previous section, the differential diagnosis in many of these instances of potential false positives may be mistaken for changes at risk for being false negative.

The main causes of false positive cytology

|