Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of cervix – high-grade CGIN

Although typical cytological features of AIS can be described and recognised, it is impossible to exclude the presence of invasion when these features are seen. In the UK system, high-grade CGIN (AIS) and endocervical adenocarcinoma are collectively described as glandular neoplasia: when glandular neoplasia is diagnosed on cytology invasive carcinoma may already be present. As with squamous cell carcinoma, there are cytological features to suggest that adenocarcinoma may be invasive.

It is important to recognise the cytological features of glandular neoplasia and to be able to distinguish it from HSIL although AIS/CGIN frequently coexists with high-grade CIN. The management of CGIN is different from that of CIN and may be difficult to visualise at colposcopy. [Link to Chapter 12 – Cytology in a multidisciplinary setting]

Presentation

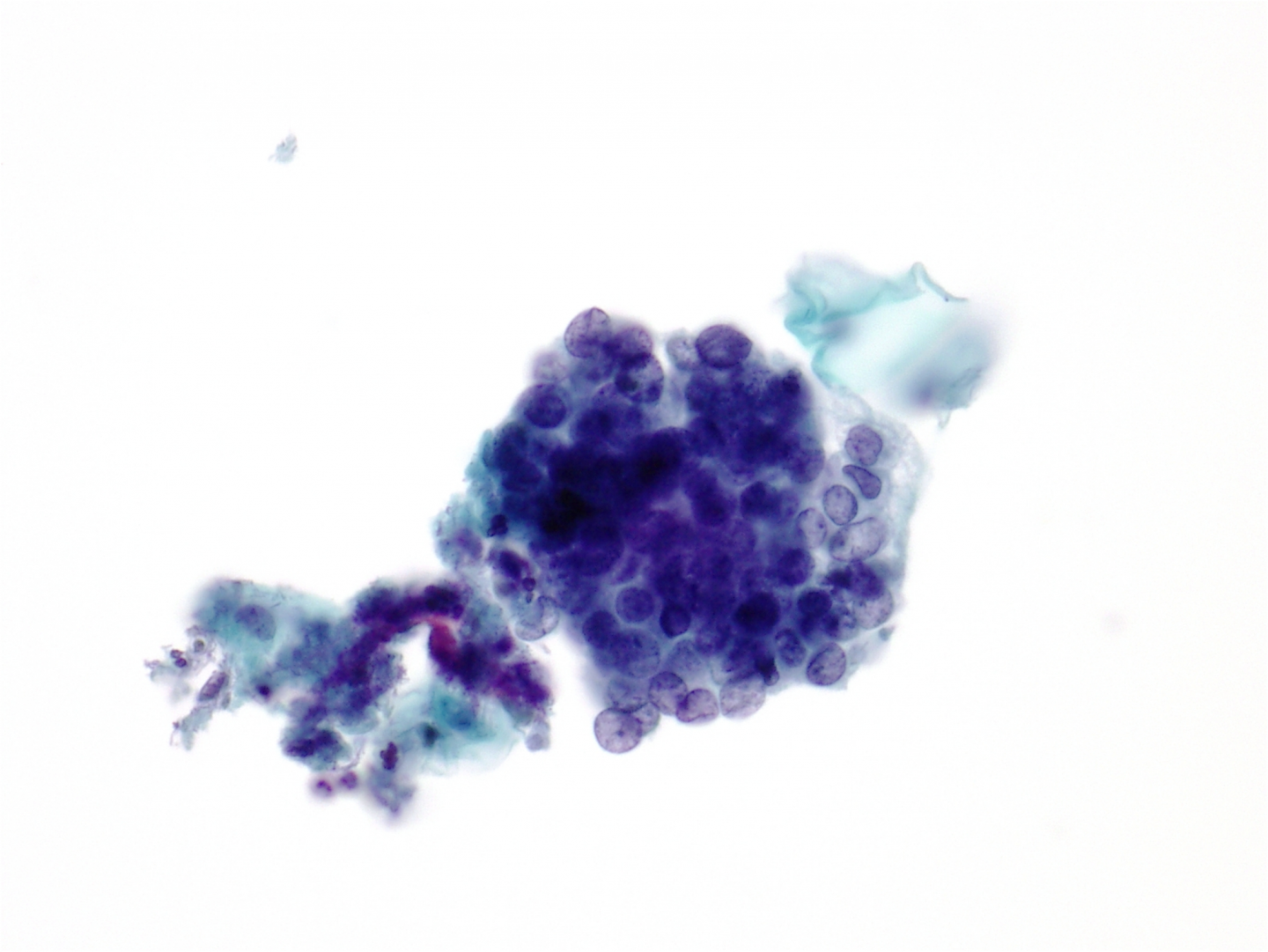

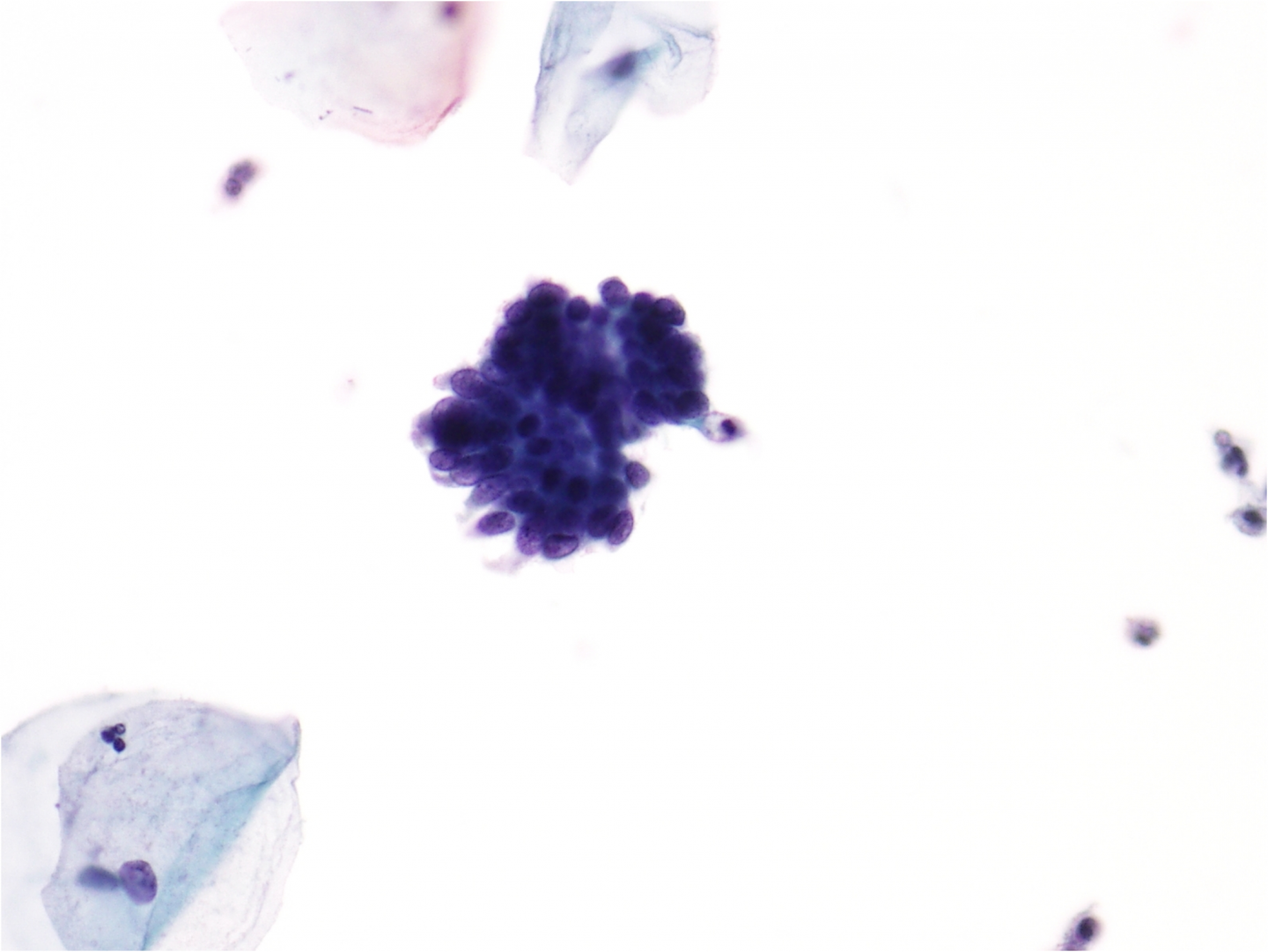

In glandular neoplasia normal endocervical cells are usually present along with the abnormal ones allowing the cytologist to compare them with each other. In AIS the architecture of the groups is disturbed: the normal honeycomb pattern of endocervical cells seen from above and their ‘picket fence’ appearance from the side due to the basally situated nuclei of columnar cells is lost. The nuclei are crowded and situated at different levels in the epithelium (pseudostratification) although the polarity of columnar cells is largely maintained. The cells present as sheets, strips or clusters – with some loss of cohesion at the surface of the cell groups. Isolated cells are not a feature of AIS and its recognition largely depends on the architecture of the cell groups. The nuclei tend to be elongated, and the loosely cohesive cells at the surface of the curved cell groups tend to be tapered and spread out rather like feathers on a wing tip: a feature known as feathering. Some groups have areas where a lumen (acinus) appears to be forming; this is a feature that helps to indicate the glandular origin of the cells. Rosette formation, where all the nuclei line up like petals to form acini, is also a feature of a glandular neoplasia.

Nucleus

The nuclear features depend on the degree of differentiation and the type adenocarcinoma. In typical AIS the nuclei are round to oval or elongated. The chromatin pattern is fine or moderately granular with even distribution. Nucleoli are usually small or inconspicuous and may not be present.

Cytoplasm

In well-differentiated endocervical adenocarcinoma or AIS the cytoplasm resembles that of the normal glandular epithelium from which it arises. The cytoplasm is columnar, delicate and may be vacuolated due to mucin secretion.

Poorly differentiated AIS

AIS may be poorly differentiated and show features more often seen in invasive adenocarcinoma from which it cannot be distinguished. The cells are in three-dimensional clusters, nuclei enlarged and round with prominent multiple nucleoli. Alternatively, poorly differentiated AIS may look similar to non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma.

| Invasive and in situ endocervical adenocarcinomaAlthough the typical appearance of AIS can be recognised, there are no cytological criteria for excluding invasionThe term ‘glandular neoplasia’ in the UK system refers either to invasive or in situ adenocarcinomaInvasive adenocarcinoma has a variety of cytological appearances depending on the cell type and degree of differentiationAs with squamous cell carcinoma there are certain cytological features that may suggest the presence of invasion |

Typical appearance of glandular neoplasia may be examined as a scanned LBC slide [Link to win.eurocytology.eu/virtualslides/gyn/vs-015]

Figure 9c-23 (a-c). Typical features of AIS

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix

The commonest form of adenocarcinoma of the cervix is mucin-secreting endocervical-type adenocarcinoma, which is often preceded by AIS or coexists with it. Endocervical cell carcinoma may also be endometrioid, intestinal, clear cell or minimal deviation. These types of carcinoma are seldom diagnosed on cervical cytology but may explain unusual appearances of glandular neoplasia. Rather than directly sampled by a spatula, broom or brush, adenocarcinoma, particularly from the endometrial cavity or elsewhere in the genital tract, is more likely to exfoliate by malignant cells detaching from the tumour and passing down the endocervical canal. Exfoliated adenocarcinoma cells tend to ‘ball up’ when in a fluid or mucoid environment and appear as 3-dimensional cell clusters. Directly sampled tumours involving the endocervical canal or external os have a ‘freshly sampled’ appearance: the cells are not degenerate and are likely to be abundant. Cytology is not usually carried out on clinical symptomatic cancers. Invasive adenocarcinomas that are directly sampled are more likely to be early occult carcinomas. Cytological features of invasive adenocarcinoma are most usefully considered in three categories:

- Endocervical carcinoma with features suggesting invasion

- Endometrial carcinoma exfoliated from the endometrial cavity

- Extra-uterine adenocarcinoma in cervical cytology

1. Endocervical carcinoma with features suggesting invasion

Presentation and cytopathology

Adenocarcinoma, especially when directly sampled, tends to present as large or small tissue fragments and sheets of cells throughout the sample. There is exaggerated nuclear crowding and the tissue fragments are disorganised. The normal endocervical honeycomb appearance is lost but mucin vacuoles may indicate the type of adenocarcinoma. There are few single, dispersed cells. The features of AIS may also be present.

The delicate cytoplasm may be plentiful, the nuclei eccentric and mucin vacuoles and columnar morphology may be retained.

The presence of red blood cells, changed blood and necrotic debris may suggest invasive carcinoma.

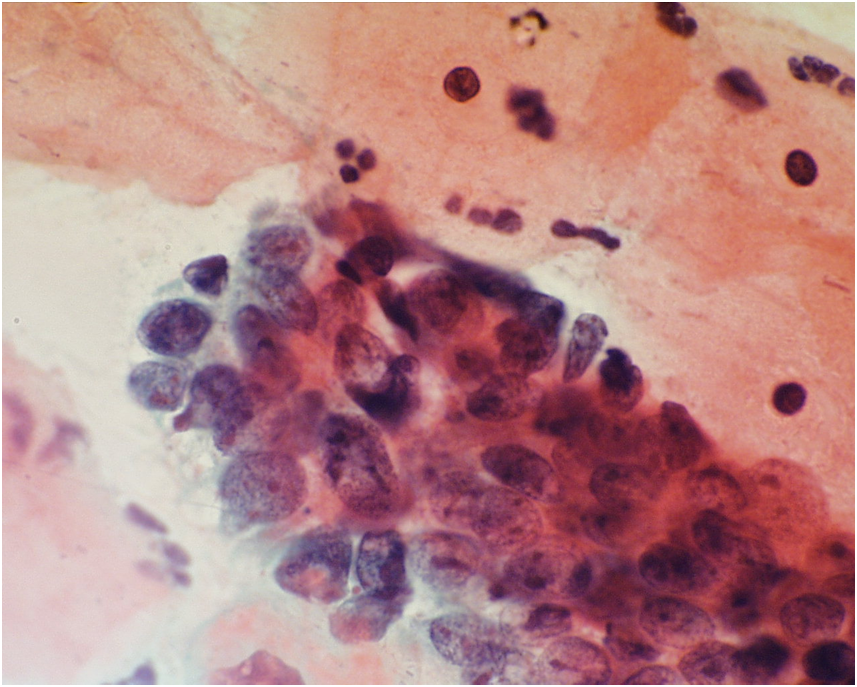

Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma has relatively uniform nuclei similar to that seen in AIS from which it cannot be distinguished. The nuclei are round to oval in shape and are hyperchromatic but the chromatin finely granular and evenly distributed. The nuclear membrane is regular in outline but may be poorly defined.

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma shows features that may suggest the possibility of invasive carcinoma although the poorly differentiated form of AIS would look similar. Nuclei tend to be round, pleomorphic and enlarged with variation of cell size within cell groups. Nuclei may be hypochromatic with unevenly distributed chromatin and nuclear clearing. Nucleoli are prominent and may range from small to large, irregular and/or multiple. Mitotic figures are likely to be frequent. Multinucleation is a common feature.

Endocervical carcinoma may be endometrioid in type, which presents a rather different appearance, which may be mistaken for hyperplastic or neoplastic endometrial cells from the uterine cavity. As with other forms of cervical glandular neoplasia it may coexist with squamous CIN. .

Figure 9c-24 (a-b) Invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma

(a) Invasive adenocarcinoma with pale vesicular nuclei in a three-dimensional cluster.

2. Endometrial carcinoma exfoliated from the endometrial cavity

The commonest non-cervical adenocarcinoma to be seen in cervical cytology samples is endometrial carcinoma, which infrequently may be found on routine cytology samples in women without symptoms. Endometrial carcinoma is more often diagnosed through the investigation of symptoms, particularly post-menopausal bleeding, in which case cytological samples are unlikely to be taken. Endometrial carcinoma is seldom seen in women below 40 years of age.

Presentation and cytological appearance

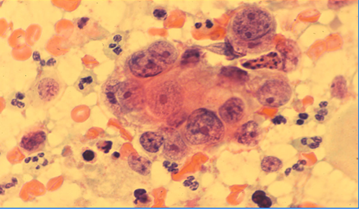

Endometrial carcinoma is exfoliated so the cells may be degenerate, few in number and presenting as small, rounded clusters of atypical glandular cells. The nuclei tend to be pale, vesicular and eccentric with prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm is also pale staining and typically contains ingested neutrophil polymorphs.

The background of the cervical epithelial cells is usually clean and the cell pattern in a post-menopausal woman may be oestrogenised.

A distinction cannot be made on cytology between endometrial carcinoma and atypical endometrial proliferation.

Figure 9c-25. Endometrial adenocarcinoma

Endometrial carcinoma with eccentric nuclei and acinar formation in a conventional cervical smear.

- 3. Extra-uterine adenocarcinoma in cervical cytologyAdenocarcinoma may exfoliate from the peritoneal cavity, ovaries or fallopian tube typically presenting as three-dimensional papillary clusters of cells in a clean background. Breast carcinoma, particularly invasive lobular carcinoma, may metastasise widely and be seen in cervical cytology samples. The appearance of the cells depends on the cell or origin and degree of differentiation. Diagnosis depends on recognising adenocarcinoma cells whose origin is determined from the clinical history. Ovarian carcinoma is the commonest extra-uterine carcinoma to be seen in Pap smears. Figure 9c-26 (a-c). Serous ovarian carcinoma in a Pap smear Atypical glandular cellsAs described above there are plentiful mimics of glandular neoplasia, which may occasionally justify reports of atypical glandular cells or borderline changes in endocervical cells. These should be rare if the typical appearances of AIS are recognised, features suggesting invasive adenocarcinoma looked for and clinical presentation taken into account. The main problems leading to a report of AGC result from misinterpreting reactive changes in endocervical cells. The latter may show mucin depletion and shrinkage of columnar cytoplasm in which case they present similar problems to immature metaplastic cells. [Link to Chapter 9b – Normal and reactive changes]Where there is uncertainty about the diagnosis or AIS or adenocarcinoma, the term AGC favour neoplasia is used in TBS.Reports of AGC should explain the dilemma in a free text report and specify whether the atypical cells are endocervical, endometrial or other types of cells.

| Learning points from Chapter 9cEffective cervical screening depends on cytologists recognising abnormal cells in a background of many thousands of normal cellsDyskaryosis, which is a descriptive term for the nuclear changes of SIL, depends on an abnormal nuclear chromatin pattern and irregular nuclear membranes.Increasing nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio is the main feature distinguishing low-grade from high-grade SIL.Mitotic activity, hyperchromasia, nuclear enlargement and multinucleation may be seen in dyskaryotic cells but these features are variable and not in themselves diagnostic of SIL.Koilocytosis is a feature of productive infection by HPV, which cannot reliably be distinguished from CIN1 on histology or from LSIL on cytology.The majority of LSILs are caused by HPV whether or not koilocytosis present.Nuclei tend to be larger in LSIL than HSIL and the increased NC ratio is largely due to reduced cytoplasmic size reflecting incomplete maturation of the squamous cells.The term ASC-US is used when it is genuinely difficult to distinguish benign, reactive or degenerative changes from LSIL or HPV.HSIL may present as hyperchromatic crowded groups of cells in which the nuclear changes are best seen at the margins or in separated cells between the crowded groups.HSIL nuclei may be hyper or hypochromatic: diagnosis depends on the chromatin pattern and nuclear membrane irregularity.ASC-H should be used sparingly but can avoid false positives and false negativesInvasive carcinoma cannot be diagnosed on cytology alone but certain features such as tumour diathesis may suggest invasion.Although the typical appearance of AIS can be recognised, there are no cytological criteria for excluding invasion or for separating in situ from invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma. |